The aim of this magazine is to connect the communities of Hindu Kush, Himalaya, Karakorum and Pamir by providing them a common accessible platform for production and dissemination of knowledge.

The past and present of Gawri language

Abstract

In 1921, George Grierson, the editor of the Linguistic Survey of India, wrote the following words about what we now call the “Kohistani” languages of northern Pakistan: “These languages are being gradually superseded by Pashto, and are dying out in the face of their more powerful neighbor. Those of the Swat and Indus Kohistans are disappearing before our eyes.” (Grierson 1921:124). More than 85 years later, there should be little left of these languages. However, Grierson was too pessimistic. Today, languages such as Gawri, Torwali, and Indus Kohistani, are still around, their populations have grown, and many of their children are still learning the languages.

This is not to say that these languages are entirely out of danger. On the contrary, the forces at work in recent decades may be more dangerous than those that Grierson was observing in his days. Fieldwork in (2003), for instance, shows that in two sizeable villages, an almost complete shift has taken place from Gawri to Pashto, so that people over 30 or 40 years can still speak Gawri, but the younger generations cannot.

In this paper we will report on efforts to strengthen the Gawri language through a multilingual education programme for children. This programme builds on earlier efforts in linguistic research, orthography development, and vernacular literature production; these efforts are characterised by

a growing interest and contribution from the community itself.

The Gawri language community

The country of Pakistan is known for its colorful diversity of cultures and languages. This ethnic diversity characterizes the country as a whole, but culminates in the mountainous North, where fast-flowing streams and high mountain ranges create natural barriers that impede mobility and communication.

One of the people groups in that area are the Gawri, a unique linguistic and ethnic group with a long history, who about a thousand years ago were pushed back by invading Afghan armies from the fertile, lower areas, up to the rugged, upper reaches of mountain valleys, in an areas Kalam, Utrot and Dir Kohistan. Nowadays, the Gawri struggle hard for their existence, in a country where two-thirds of the population lives in modest to extreme poverty anyway.

For Gawri children, education is essential if they are to have opportunities when they grow up to find work and earn an income. However, these children do not speak the general languages when they enter school, and often drop out of the current school system because they do not understand the languages in which the subject matter is taught.

Linguistic environment

Gawri is one of about two dozen languages that are spoken in the mountain areas of northern Pakistan. This language is spoken in the Kalam valley in district Swat, and also in the Kohistan tahsil in district Dir, in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. Other languages such as Kalkoti, Gojri, Torwali, Indus Kohistani (Mayo), and Pashto languages are also spoken the area.

Traditionally, the Gawri-speaking area in Swat is divided into three major clus¬ters of villages and hamlets, each named after its principal village: the lower cluster is Kalam proper; up from Kalam there is the Utrot clus¬ter in the West, and the Ushu clus¬ter in the North-East. The three commu¬nities have different traditions regarding their historical descent, and each has its own po¬litical organisation.

Although the dialect of Utrot and the dialect of Ushu are per¬ceptibly different from each other and from the dialect of the Kalam clus¬ter, all three are very much the same lan¬guage, in the opin¬ion of the people as well as according to more formal sociolinguistic criteria (see Rensch 1992).

As mentioned above, the language is spread over a larger area than just Kalam valley. When one crosses over the mountains westward from Utrot, one reaches the upper part of the Panjkora valley, which belongs to district Upper Dir. This area is often called Dir Kohistan. Here too, in a number of villages—Thal, Lamuti, Barikot, Biar, Kalkot and Raj¬kot/Patrak—the same Gawri language is spoken.

Geographical area

Kalam Kohistan is the name given to the northern-most parts of the Swat district in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, including Kalam and the areas beyond Kalam. To the North it is bordered by the moun¬tains of Chitral and the Gilgit-Baltistan. To the East, several high mountain passes lead into the Kandia valley of Indus Kohistan. Fre¬quently-travelled mountain passes also connect to the West, to the vil-lages of Thal and Lamuti in Dir Kohistan. Kalam is the name of a village located at the confluence of the Ushu and Utrot rivers, which form the river Swat in Kalam. The Gawri also known as Kalam Kohistani people occupy most of the upper-most parts of the Swat valley. However, some of the highest permanent settlements are not inhabited by Gawris but by Gujars, who speak their own language, Gujari.

Kalam village is located at an altitude of approximately 7,000 feet above sea level. The scenery in Kalam is dominated by the glaciers of the nearby Kushujan i.e. Mankial range, east of Kalam, and by the more distant peak of the Palsaar commonly known as Falakser. The peaks of Mankial and Falakser reach an altitude of just under 20,000 feet.

Upper Dir District, of which Dir Kohistan forms a part, is also in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. Chitral borders it in the North, Swat in the East, Afghanistan and Bajaur in the West, and Malakand in the South. The Gawri people of Dir live in the north¬ern part of the upper Dir district, in the upper reaches of the Panjkora valley. A jeep road leading from Lamuti over a mountain pass to Utrot in Kalam Kohistan connects the Gawri people across both the borders. This jeep-track is open in summer.

Population

Stahl (1988:40) and Rensch (1992:33) estimate the number of Gawri speakers in Swat to be 40,000. The Kalam Integrated Development Project(KIDP), which worked in the area for more than a decade, gave an estimated, supposedly more reliable than the 1981 census figures, total population of Kalam valley around 40,000 in 1982. However, from this figure we have to subtract the population of the non-Gawri speaking communi¬ties in Kalam valley.

On the basis of the KIDP data, we arrive at a number of between 26,000 and 30,000 mother-tongue speakers of Gawri in Kalam tahsil in 1982. Assuming an average annual popula¬tion growth rate of three percent, which roughly approximates the figure for Paki¬stan as a whole, the number of Gawri mother-tongue speakers in Kalam tahsil in 1995 may have been in the range of 38,000 to 44,000. To this we need to add the Gawri-speaking population of Dir Kohis¬tan and the Dachwa speakers in Ariani, the eastern village opposite Peshmal in Bahrain tehsil.

According to Keiser (1986:493) the population of village Thal in Dir Kohistan was approximately 6,000 in 1984. In July 1995, two men from Kalam visited Dir Kohistan and on our request inquired about numbers of Gawri speak¬ers. Based on the number of forest royalty shares, the number of Gawri speakers was said to be 8,000 for those living in Thal, 7,000 for Lamuti, and 2,000 for Kalkot. We do not have up-to-date fig¬ures for the other Gawri-speaking villages, Barikot, Biar, Patrak, in Dir Kohistan. On the basis of the available information, the total num¬ber of mother-tongue speakers of Gawri, including both Swat and Dir Kohistan, may be estimated to be in the range of 60,000 to 70,000 in 1995.

Current figures are not very clear but according to some sources Gawri language speakers easily surpassed 100,000, because they live in majority in two union councils in Swat and five in Dir Kohistan.

Names of the language

In the linguistic and ethnographic literature, the language has been given differ¬ent names. Morgenstierne (1940) uses the name Bashkarik, a name that was also used by Biddulph (1880/1971:70,71). Grierson in the Linguistic Survey of India (LSI 8/2:507ff) called the language Garwi (ga:rwi:). Barth (1956:52) and Barth & Morgenstierne (1958:120) gave Gawri as a more accurate version of the latter and also found that the name Bash¬karik is not known by the Gawri speakers in the Kalam area. Rensch (1992:5) and his co-workers found that the name Gawri was regarded as pejora¬tive by some speakers of the language. Rensch and his co-workers use Kalami and Kalami Kohistani in their work. The name Bashkari is used by Khowar speakers in Swat Kohistan for speakers of Gawri, while the Gawri language is called Bashkarwar in Khowar.

Apparently both these names, Gawri and Bashkari, have a long his¬tory. The name Gauri occurs in the Vedas, and in the work of Panini (late 5th or early 4th century BC) and other Indian sources, as a name of the river Panjkora in what is now district Dir. In 327 BC Alexander the Great fought a battle in this area at a place called Massaka, with a tribe called the Gau¬¬raioi (also called Gretai). In the work of Ptolemy (c. 150 AD), the region directly to the west of the river Swat is called Goryaia (see Schwartzberg 1992 for more information on these refer¬ences). About the tribal name Bashkar, Bloch (1965:23) says that it is a relic of the Vedas and “no doubt the same as that of the school, which preserved the Rgveda.”

The Gawri-speaking people themselves most commonly use the name Kohistani to refer to their language. Originally the name Kohistani was used by the Pathans that lived in the lower parts of the Swat valley for the tribes that lived higher up. (Biddulph 1880/1971:69; Barth 1956:52).

History

The predecessors of the Gawri-speaking people are perhaps the same as the Gauraioi (Gawri), who inhabited the lower, more fertile parts of Dir from as early as the days of Panini and Alexander the Great, as mentioned above. In the 11th century AD, the area was con¬quered by Afghan troops under Mahmood of Ghazni and the original population was forced to flee to the remote, mountainous parts of the Panjkora valley. Local traditions confirm that from there, groups of Gawri settlers passed over across the mountain passes into the Utrot, Kalam, and Ushu valleys in what is now district Swat, while others stayed in the upper Panjkora valley.

From the 14th century onward, a new wave of Afghan invaders, the Yusufzai Pathans, gradually took over the lower parts of Dir and Swat. Under pressure from the Yusufzais Pathans that had settled there before fled the area, and some of them arrived in the upper reaches of the Swat and Panjkora valleys. Due to the influence of these Muslim immigrants, the Kalam and Dir Kohistanis converted to Islam, proba¬bly in the 15th and 16th centuries.

The Kalam Kohistanis have been able to maintain a large degree of political independence for many centuries. Finally, in 1947, when the British left India, the Wali of Swat was able to establish his rule over Kalam Kohistan for a short span of time. Later in 1954, the then Pakistani government took Kalam from Wali of Swat and maintained it as a tribal territory until 1969 when it was merged with Pakistan along with the State of Swat. The Wali built roads, schools, and hospitals in the area. Subsequently, Swat was incorporated as a part of Pakistan in 1969.

Till the present day, the people of Kalam and Dir Kohistan have retained their inde¬pendent spirit. In many ways tribal tradi¬tions still take precedence over official Pakistani law.

Socio-economic conditions

Traditionally the Kalamis were subsistence farmers. Some thirty or forty years ago, potato was introduced as a cash crop and adopted by almost all farmers. Nowadays, one can see a few other cash crops as well, such as turnip and cabbage.

Due to increasing population pressure, the Kalami people are forced to look for other sources of income besides agriculture. In the winter sea¬son, many Kalamis travel to Mingora, Peshawar, Rawalpindi, Lahore, and other cities of Pakistan, in search of livelihood.

In the 1980s and 1990s, there has been an explosive growth of tourism in Kalam. There are presently more than 200 hotels in the Kalam area. Tourism does create income for the Kalamis: some find jobs in hotels and restaurants, some earn an income as guides and jeep drivers, or as shopkeepers catering to the tourists. Unfortunately, only a few hotels are owned by Kalamis; most are owned by outsiders, and most of the income from tourism is not go into the pockets of the local people.

Probably less than ten percent of the Kalami men and very few women have received education. Government schools are operating in the larger villages of the area, but due to a lack of teachers and lack of facilities, the quality of education is poor. In 1996, a private school was opened in the Kalam area that is run on a commercial basis. Two other such schools were established in 1997. These commercial schools have been quite successful in attracting sizeable numbers of students.

There are only two function¬ing primary schools for girls in the entire area. A pro¬gramme of home tuition centres for girls was started by KIDP around 1990. This programme gained some popularity with the local people. However, after the closure of the KIDP in 1998, these centers are no longer functional. In the schools, as well as in the home tuition centres, the medium of educa¬tion is Pashto. To the younger children, teachers often provide verbal explanation in the Gawri language as well. The higher grades in school are taught in Urdu.

Relationship to other languages

According to its genetic classification (Strand 1973:302), Gawri belongs to the Kohistani branch of the Dardic group of lan¬guages, along with several closely related languages in its geographi¬cal vicinity: Kalkoti (spoken in the village of Kalkot in Dir Kohistan), Torwali (in Swat Kohistan south of Kalam), Indus Kohistani, Bateri, Chilisso, and Gowro (the latter four in Indus Kohistan). Dardic in turn also includes such languages as Pashayi across the border in Afghani¬stan, Khowar and Kalasha in Chitral, Shina in the Northern Areas, and Kashmiri in AJK and across the line-of-control.

Dardic languages belong to the Indo-Aryan language group, which means that they are genetically more closely related to Urdu, Punjabi, and Sindhi, than for instance to Pashto and Balochi, the latter two being Iranian languages. Within Indo-Aryan, Dardic is related more closely to Hindko, Punjabi, Sindhi, and Siraiki, which are said to belong to the north-western zone of Indo-Aryan, together with Dardic. Urdu, the main literary language, and Gujari, which is also spoken in the Kalam and Dir Kohistan areas, are somewhat more distant, as these languages belong to the central rather than the north-western zone of Indo-Aryan (see Masica 1991:446ff. for a discussion of Indo-Aryan sub-classification).

Of course, similarities between languages do not only arise because of genealogical relatedness, but also under the influence of other factors, such as language contact. One general observation is that Gawri shares a number of features with most other languages within the South Asian linguistic area, be they Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, Iranian, or even the isolate Burushaski.

Finally it is no surprise to find that many words have been borrowed into the Gawri language from languages of particular religious, political, or economic importance, notably Arabic, Persian, Pashto, English, and Urdu.

Literature on the Gawri language

Prior to our own research, few linguistic descriptions of Gawri had been published (Leech 1838, Biddulph 1880, LSI 1919, Morgenstierne 1940, Morgenstierne & Barth 1958). The most extensive treatment in the English lan¬guage was Morgenstierne (1940), which has 17 pages of text followed by a 35-page word list. The actual field work on which that treatment was based was carried out in 1929, and his prin¬cipal language consultant was from Lamuti in Dir Kohistan.

More recently, a sociolinguistic survey of Kalam and surround¬ing areas has been carried out by Rensch and co-workers (Stahl 1988, Rensch 1992). These stud¬ies focus on bilin¬gualism and language use, but give little information on the lan¬guage itself.

Quite rich in information is Shaheen (1989), which is written in Urdu and discusses the history and languages of the Kalam area at a popular level. He devotes many pages to a list of Gawri words and phrases.

Dr. Joan Baart a renounced linguist and a pioneer of Gawri language research have written many books. These were sound system, grammar, Gawri texts, and uses of plants in Kalam Kohistan of the Gawri.

Gawri Community Development Programme (GCDP) itself and with the help of Forum for Language Initiatives (FLI) also published many vernacular books in Gawri such as proverbs, conversation book, history of Kalam, story books, alphabet books, primer and other literacy materials for the Mother Tongue Based Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE) schools. Literary publications in the Gawri language are by Abdul Haq (1997), Sagar (1998), and Lal Badshah (2000). For a published version of Abdul Haq’s history of Kalam see Mankiralay (1987).

“Mr. Abdul Haq was a man of many careers. The people call him “Maulana” because he is a religious scholar of high standing, to whom people from far-away places come to seek guidance and to be cured from their ailments. He is an innovator who was the first to introduce the growing of potatoes in his village. He is also a scholar of history, who has compiled a number of hand-written works, in Pashto, about the political history of Kalam. One of these works has even been published in Germany in an English translation. Finally, he is famous as a poet. His songs, most of which are composed in the Gawri language, are extremely popular among the local people.” These are the words of Dr. Joan Baart about Maulana Abdul Haq (late), one the most respected religious leaders, historians and poets of Gawri language.

The Gawri Community Development Program and its Multi-Lingual Education (MLE) project

The Gawri Community Development Program (GCDP) is a local, officially registered, non-governmental organization which is dedicated to community development in the valleys of Kalam and Utrot through provision of education and health services.

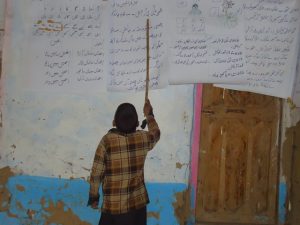

Among other activities, GCDP is currently engaged in a significant effort in the Kalam area, which aims at the introduction and acceptance of mother-tongue-based multi-lingual education (MLE). In the classes administered by this project, children begin to learn to read, write, and do math in their own native language (Gawri), while in the course of the program the important languages of wider communication, Urdu and English, are gradually introduced.

In August 2008, two pilot schools were started in the Kalam area. The teachers in both schools used multi-lingual curriculum materials that had been developed by the project team. By April 2011, the first batch of students finished the 3-year program, and many of them are now continuing their education in grade 2 (or higher) in the government school system. Also as of April 2011, four new MLE classes have been started in different locations in the Kalam area, catering to a total of approximately 100 young students.

Whereas the initial MLE efforts were regarded with indifference, if not hostility, by most of the Gawri community, now that the classes are in operation and students who have gone through the programme do well in the government school system, a watershed change of attitude seems to be currently in progress in the community, as witnessed by requests being received for more MLE classes, as well as an overwhelming attendance—more than 250 people from the community—exceeding anything the organizers had anticipated, at a function organized this year by the MLE project to celebrate World Literacy Day.

References

Baart, Joan L.G. 1997. The Sounds and Tones of Kalam Kohistani; With Wordlist and Texts. Islamabad: National Institute of Pakistan Studies and Summer Institute of Linguistics. (Studies in Languages of Northern Pakistan Vol. 1).

Baart, Joan L.G. 1999a. Tone Rules in Kalam Kohistani (Garwi, Bashkarik). London. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies Vol. 62, No. 1: 87 – 104.

Baart, Joan L.G. 1999b. A Sketch of Kalam Kohistani Grammar. Islamabad: National Institute of Pakistan Studies and Summer Institute of Linguistics. (Studies in Languages of Northern Pakistan Vol. 5).

Baloch, N.A. 1966. Some Lesser Known Dialects of Kohistan. Dacca: Asiatic Society of Pakistan. Haqq, Muhammad Enamul (ed.): Shahidullah Felicitation Volume, pp. 45 – 55.

Barth, Fredrik. 1956. Indus and Swat Kohistan; an Ethnographic Survey. Oslo.

Barth, Fredrik & Georg Morgenstierne. 1958. Vocabularies and specimens of some S.E. Dardic dialects. Norsk Tidskrift for Sprogvidenskap 18:118-136.

Biddulph, John. 1880. Tribes of the Hindoo Koosh. Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, Graz. Reprint 1971.

Bloch, Jules. 1965. Indo-Aryan; from the Vedas to Modern Times. English edition, largely revised by the author and translated by Alfred Master. Paris.

Greenberg, Joseph H. 1963. Some universals of grammar with particular reference to the order of meaningful elements. In Joseph H. Greenberg (ed.), Universals of Language. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Haq, Maulana Abdul. 1997. Kalami Ramuze Ashaar; (Kalami Poetry). Kalam, Swat: Kalam Cultural Society.

Karimi, Abdul Hamid Khan. 1995 (c1982). Urdu-Kohistani Bol Chaal; (Urdu-Kohistani Conversation). Bahrain, Swat: Kohistan Adab Academy.

Keiser, Lincoln. 1986. Death enmity in Thull: organized vengeance and social change in a Kohistani community. American Ethnologist 13:489-505.

Keiser, Lincoln. 1991. Friend by Day, Enemy by Night; Organized Vengeance in a Kohistani Community. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Fort Worth, Texas.

Lal Badshah. 2000. Soeele~ Laang; (Autumn Mist; Kalami Poetry). Kalam, Swat: Kalam Cultural Society.

LSI: Grierson, George A. 1919. Linguistic Survey of India 8/2:507 ff. Calcutta.

Leech, R. 1838. Epitome of the grammars of the Brahuiky, the Balochky and the Panjabi languages, with vocabularies of Baraky, the Pashi, the Laghmani, the Cashgari, the Teerhai, and the Deer dialects. Journal of the Asian Society of Bombay 8.

Mankiralay, Abd al-Haq Jashni. 1987. A political history of Kalam Swat, Part I. (Translated from Pashto by A. Raziq Palwal). Zentralasiatische Studien des Seminars für Sprach- und Kulturwissenschaft Zentralasiens der Universität Bonn 20: 282-357.

Masica, Colin P. 1991. The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Morgenstierne, Georg. 1940. Notes on Bashkarik. Acta Orientalia 18:206-257.

Rensch, Calvin R. 1992. Patterns of Language Use among the Kohistanis of the Swat Valley. Islamabad: National Institute of Pakistan Studies and Summer Institute of Linguistics. Rensch, Calvin R., Sandra J. Decker and Daniel G. Hallberg: Languages of Kohistan (Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Vol. 1), pp. 3 – 62.

Sagar, Muhammad Zaman. 1998. Kalam Kohistani Matil; (Kalam Kohistani Proverbs). Kalam, Swat: Kalam Cultural Society.

Schwartzberg, Joseph E., ed. 1992. A Historical Atlas of South Asia. Oxford University Press, New York & Oxford.

Shaheen, Muhammad Parwesh. 1989. Kalam Kohistan; Log aur Zabaan. Shoaib Sons Publishers/Booksellers, GT Road, Mingora (branch Udayana Bazaar).

Stahl, James Louis. 1988. Multilingualism in Kalam Kohistan. University of Texas at Arlington. (M.A. Thesis).

Strand, Richard F. 1973. Notes on the Nuristani and Dardic languages. Journal of the American Oriental Society 93/3: 297-305.